Several years ago, I started this project with the hope of compiling a comprehensive look at the architecture of the Sonoran Desert region of Arizona. The project is currently moving through the publication process and the resulting book will be out towards the end of 2025. In the meantime, please enjoy the book’s Preface below along with a selection of images I took while exploring buildings in the region.

To purchase the book, please click on the links below to be taken to its respective pages on Routledge and Amazon.

Constructing Arizona | Routledge

Preface | A Tectonic Trajectory

The Trajectory Backward

A desert building should be nobly simple in outline as the region itself is sculptured: should have learned from the cactus many secrets of straight-line-patterns for its forms, playing with the light and softening the building into its proper place among the organic desert creations – the man-made building heightening the beauty of the desert…[i]

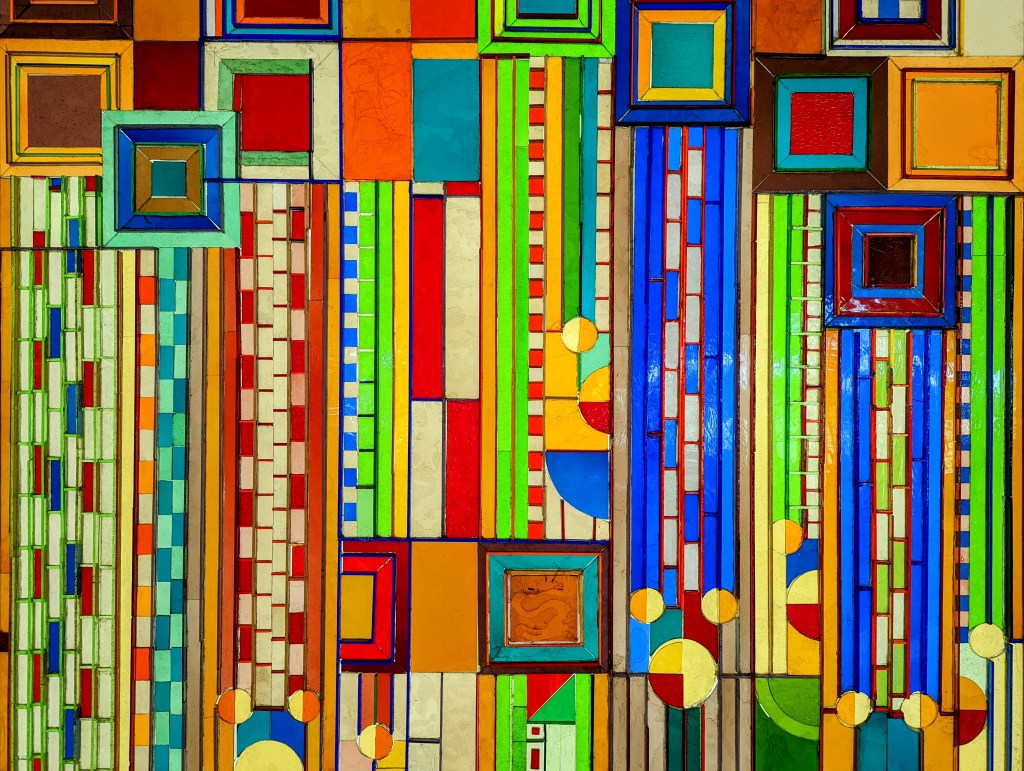

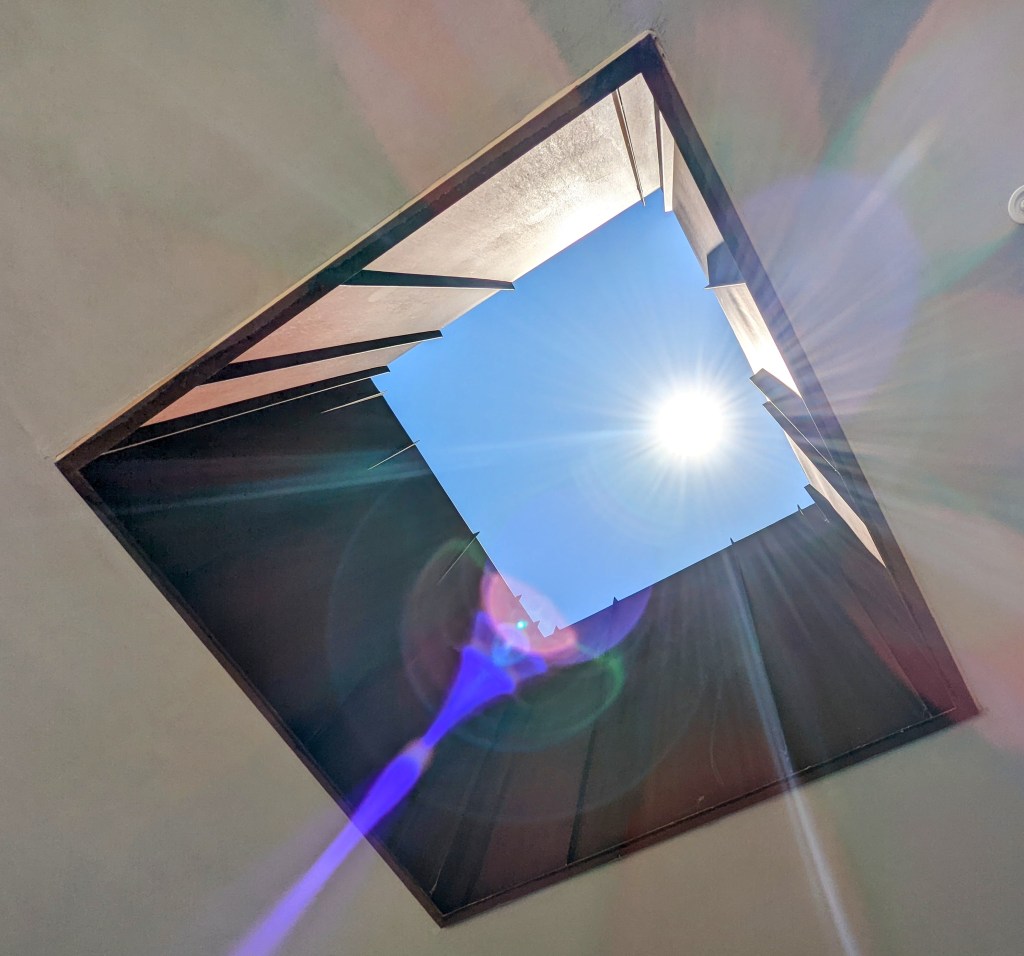

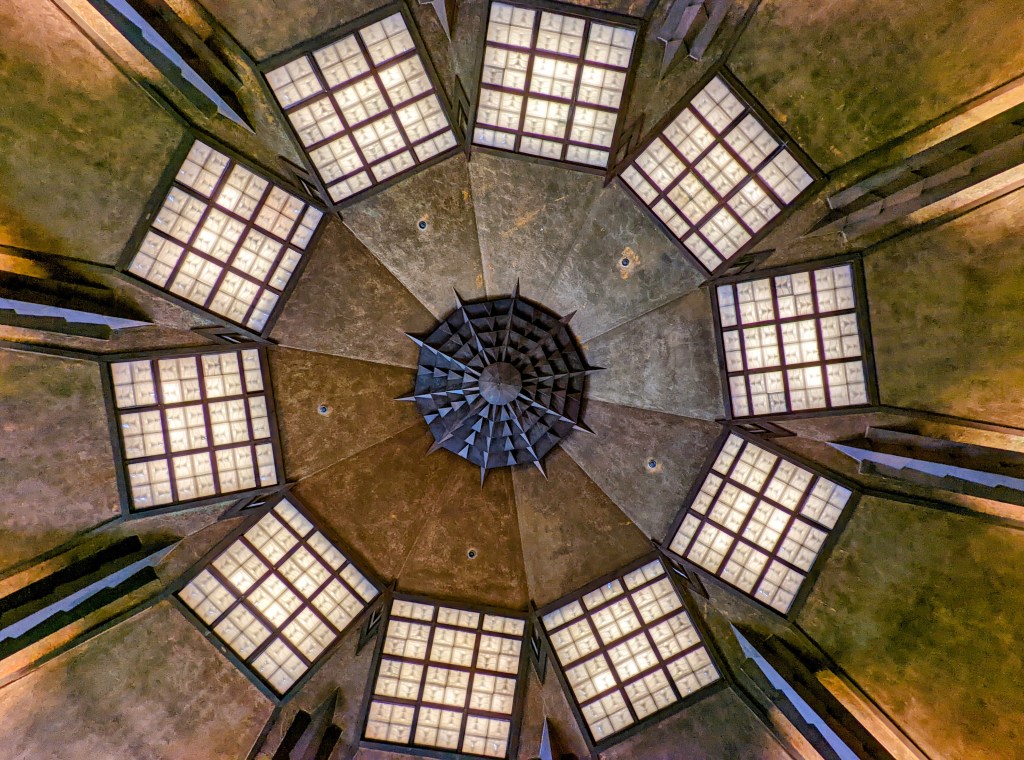

In the winter of 1928, Frank Lloyd Wright made his first pilgrimage to Arizona to consult on the design of Albert Chase McArthur’s Arizona Biltmore Hotel and was captivated by the natural beauty of the (mostly) unspoiled grandeur of the Sonoran Desert. He made several more trips to the Phoenix area in the following decade to live, work, and recuperate, eventually constructing Taliesin West as a winter home for his family and the Taliesin Fellowship. This western edition of the Taliesin compound, as described in Wright’s quote above, echoes the qualities of the desert. The materiality of the massive walls – made of concrete and boulders taken from the site – timber frames and “luminous canvas” panels provided an oasis ideally situated to both the physical place and the ever-present harshness of the desert environment.[ii]

In an article written for Arizona Highways in May 1940, however, Wright bemoaned the perhaps inevitable corruption of this pristine environment:

I, for one, dread to see this incomparable nature garden marred, eventually spoiled by candy-makers, cactus hunters, careless fire-builders and the fancy period-house builders, as well as the Hopi Indian imitators, or imitation Mexican ‘hut’ builders. They will soon destroy the most accessible parts unless Arizona people have the sense to stop them.[iii]

Wright’s musings appear to define much of the contemporary built environment of the Phoenix metropolitan area, where, according to journalist Lawrence Cheek, “the architectural forms most Arizonans encounter on a given day are the woozy nostalgia of the stucco subdivisions and the amorphous frenzy of the commercial strips.”[iv] These effects continue to be compounded by the migratory nature of the city, a place that, while constantly growing, has seemingly as many people on their way out as on their way in. Although certainly not without its good qualities, the banality and ever-expanding reach of this sea of humanity in the desert can be suffocating.

In “The Making of the Arizona School” – published in May 2002 in Architecture – Cheek ruminates on the past, current, and future states of the cities of the Sonoran Desert – primarily Phoenix and Tucson, AZ. He speaks of Wright’s philosophies and their similarity to those of the indigenous peoples who inhabited the region for centuries, focusing on the establishment of a graceful relationship between building and landscape. This touchstone illustrates an architectural lineage. Italian architect Paolo Soleri came to Arizona to learn from Wright at Taliesin, eventually leaving the Fellowship and founding his urban laboratory, Arcosanti. Wisconsin-born architect Will Bruder spent his early years in the region studying under Soleri before starting his practice in Phoenix. Cheek postulates that these influential individuals – along with others such as Al Beadle and Judith Chafee – contributed to the emergence of an Arizona School of architecture “that now persists” – or at least persisted in 2002 – “in the work of a scattering of modernists” practicing their craft in the heat of the Sonoran Desert.[v]

When the article came out, I was enrolled in the graduate architecture program at Arizona State University, having relocated from my home state of Illinois to experience a new place and a new environment. I was immediately taken by Cheek’s portrayal of this counterculture of rogue architects, just as I had been with the qualities of Arizona’s architecture and the beauty of the Sonoran Desert. My stay in Phoenix lasted ten years, encompassing graduate school, my formative work experiences, and my path to licensure. Needless to say, my time in the desert significantly impacted my perspective on the practice of architecture. Now, over twenty years later, this book reflects on the proposition of an Arizona School, arguing that, unlike other named Schools of architectural thought, it is not a stylistic or intellectual construct but one centered on formal and tectonic response to place.

The Trajectory Forward

Architectural tectonics involves the relationship developed between spatial experience and the underlying mechanics that make it possible. How we construct, the materials we use, and the systems we employ dramatically impact the overall experience of architecture. This research project builds on a decade of work studying the architectonic from various perspectives. In my first book, Introducing Architectural Tectonics: Exploring the Intersection of Design and Construction,[vi] readers were presented with an overview of tectonic theory organized into a taxonomy of tectonic concepts – anatomy, construction, materiality, detail, place, precedent, representation, ornamentation, space, and the atectonic – which was then deployed in the analysis of a series of contemporary precedents. My second publication, Situate, Manipulate, Fabricate: An Anthology of the Influences on Architectural Design and Production,[vii] highlighted three of these categories as the primary drivers of tectonically-centered architecture – place, material, and fabrication – through a collection of eighteen essays by notable architects and architectural theorists.

This research project continues to focus this line of inquiry, positioning place as the foundational tectonic catalyst. Within the Sonoran Desert of Arizona, the Arizona School can be characterized as a group of architects who have developed the skills and knowledge to connect their work meaningfully to the contextual conditions of that particular place. As such, this project seeks to understand how the architecture of this region has been and continues to be influenced by the tectonics of place: responsive to a harsh and relentless (yet beautiful) environment, thoughtful in the use of local labor and techniques, creatively exploiting materials and architectural detailing, and informed by a varied and unique cultural history. Although some of this exploration has come through the study of built work, there is an advantage in studying an architectural community whose members are still actively practicing: their own words, delivered firsthand, can inform and contribute to the research. Building on the knowledge gained through interviews with over fifty practitioners and other important figures connected to the architecture of Arizona, I hope that this book reveals for you the inherent principles, vocabulary, and influences of the architecture of Arizona while also tying its contemporary makeup to a lineage of building in the Sonoran Desert.

Modulating the Trajectory: An Aside

While my tectonic mindset whole-heartedly shaped this book, as I engaged with the research, the projects, and the community of architects in Arizona, I found myself exploring threads of connectivity between architecture and place that were not always grounded in tectonic theory. My initial reaction was to downplay those connections in favor of others I could position tectonically, but I soon realized that when writing a book about the relationships devised to situate work within a particular place in the world, ignoring any valuable connections made would be a disservice to everyone involved. As such, during the writing of this book, its focal point shifted from tectonics-centered to place-centered, modulating the presentation and allowing this resource to include insights into everything the architecture of Arizona has to offer.

[i] Frank Lloyd Wright, “To Arizona,” in Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings, ed. Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer (New York: Rizzoli, 1994), 35.

[ii] Neil Levine, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999), 9-10..

[iii] Wright, “To Arizona,” 34.

[iv] Lawrence W. Cheek, “The Making of the Arizona School,” Architecture 91, no. 5 (2002): 93.

[v] Cheek, “The Making of the Arizona School,” 87-88. The term Arizona School was first coined by architect, educator, and writer Reed Kroloff, who was serving as the editor of Architecture at the time this article was published and contributed significantly to the conceptual framework of this argument.

[vi] Chad Schwartz, Introducing Architectural Tectonics: Exploring the Intersection of Design and Construction (New York: Routledge, 2016).

[vii] Chad Schwartz, Situate, Manipulate, Fabricate: An Anthology of the Influences on Architectural Design and Production (New York: Routledge, 2020).